The Alarm’s latest album ‘War’ was written, produced & released in an astounding 50 days, just in time for lead singer Mike Peters’ birthday.

Lee Campbell spoke with Mike about this unique LP and some of the inspirations behind the tracks. We also delved into Mike’s incredible musical & personal journey from the band’s early days, including the very public break-up of the original line-up, his love for Wales, playing with Neil Young & Big Country and pulling off a live charity gig at Everest base camp.

So Mike, the new album, ‘War.’ What was behind this unique production and release process – can you tell us more about that?

Mike: I think it was a build-up of all the frustrations of not being able to be in an active band being locked down like the whole of the planet, indoors. A lot of misinformation, I felt. I turned off our TVs in our house, so the kids didn’t get affected by everything that was going on. We just listened to music, and I was on a Zoom call with our charity the night that the Capitol Building was occupied. And one of our board members represents some fairly high-up politicians in the American government. One, in particular, is Kevin McCarthy, who actually stood up and had a massive battle with Trump trying to get him to Tweet out to call off all these people who were in the building, and that was sort of all happening while we were on this board call with our board members.

“I’ve gotta call, my friends, here. I’ve got people in the Capitol, and there’s a creche, some kids in there”, Kevin said. All the stuff that never came out, really. So, we got a bit embroiled in it, and it just felt scary. It was just the last straw. I thought, you know, we’ve already switched this guy, the ex-American president, off our TVs – I won’t dignify him with his name. When he was doing all the things about “let’s put bleach down our throats” to kill the virus, that can have a massive impact on kids’ lives, ‘cause they’ll believe it, because of the power of being a president, it carries a lot of weight and authority, and it was being abused.

And I just felt like, oh, this is it, the world’s gone too far now, and that even the men at the top are losing it and behaving disgracefully. And I thought, well, I’d sort of put it all off, to be honest. I thought, if we’re gonna make a record, let’s not talk about COVID and Trump, he’ll be gone, and all that, who’s gonna want to know? And then I thought, well, I didn’t see any documents of it musically out there. And I thought, I just lost it at that moment. I went on our website and said, we’re gonna make a record. This is what’s triggered it. And I didn’t even tell the band. I didn’t even tell my wife, Jules. I just exploded it onto the internet and then woke up in the morning thinking, ‘what have I done?’ I haven’t even had a drink. It was a totally sober moment.

So anyway, I started phoning around the band, and when I got to George Williams, our producer, he actually said, “well, actually Mike, it’s not as crazy as it sounds. You’ve actually got five weeks of recording time and a week mixing time until it’s your birthday when you want to put the record out. So we can actually focus on two tracks a week and get the job done in time.” And I thought, yeah, but what if I don’t write all the songs! All I had was a bit of a song that I’d written before called ‘280 Ways To Start a War’, which is referenced in ‘Protect & Survive.’ It’s about the number of characters you can have in a Tweet, and I’ve seen that’s been so abused, not just by the ex-President, but by everybody.

It’s like a war of racism out there against footballers; it’s the abuse against musicians who are trying to make a living or anything. It just felt like we’ve created this really negative culture in lockdown, worse than it had ever been. We’ve lost that ability to talk face to face, and with that comes a bit of human decency. And you’re not going to call everybody out that you meet face to face, but behind your keyboard, let’s call everybody out and let’s be destructive – it’s all gone way over the edge. And I just sort of thought I had the beginnings of that song, and by the morning, it had become ‘Protect & Survive.’ And I did the demo, I went straight on the internet, and I said, Jules, film this song, we’re gonna put it right out on the internet. And she had filmed me speaking to the band, & George and we all said, let’s just make it out in the open; let people see the challenges of writing and recording a record and what actually goes into it because a lot of people think a record is made in a minute.

I mean, just a case in point, we had an email from somebody yesterday saying, “I’m really disappointed there’s no lyrics on the album, and the song titles aren’t on the sleeve” (laughing). Did you not read what we said at the beginning? You wouldn’t have a CD because I literally only finished the song until the last minute. So there’s no way we could get the lyrics on the website and everything else. People expect things so fast. No tolerance. That was part of what I wanted to convey in the record, this darker side of COVID. We’ve all become intolerant in some ways. We expect our Amazon delivery to come the next day, and if it doesn’t, “where is it!?” Like you say, I grew up in an era when if I wanted to get ‘Spiral Scratch’ by the Buzzcocks, I had to drive to a shop in Manchester that might have it. Yeah, not even drive, try to get a bus and then a train, then walk to the shop. And then you’d get it, and you’d have to wait three hours to get home even to play it. And you didn’t know what it sounded like; you just read about it in a music paper. And it was all immediate, wasn’t it, in terms of the trust that you were placing in the whole situation in the bands. And so I just felt like we needed to make a record now.

I actually have written an Alarm album that will come out later. Okay, but I was thinking, I don’t want to write about this. I want to write about what happens when we get back to life; it has relevance for then. But I thought, let’s make the record now. And let’s do a document a bit like, when Stiff Little Fingers wrote ‘Alternative Ulster’, it came out while ‘The Troubles’ were alive. If it were a look back at The Troubles, it wouldn’t have the same power, would it, it wouldn’t have the same weight, and it wouldn’t have the same authority of voice. So I thought, if we’re going to make a record, you look back at ‘Ohio’ by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. It came out when four students’ lives have been taken away or when Steve Biko was in jail when Peter Gabriel wrote ‘Biko.’ It doesn’t date the record because it’s written and released at the time. If it’s post-written afterwards, it’s nostalgic. It might date, and it might not have the same authority. So I thought, if we’re going to do this record, it’s got to come out now before the lockdown ends.

And so the album was written pretty much in 50 days?

Mike: Yeah. And to be honest, I surprised himself how well it stays together. I haven’t played it since we finished it. It’s not my way, so I’ve not really had any time to live with it personally. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. Once it belongs to the audience, I can’t affect it anymore. I’m starting to think about the next album I’ve already demoed. We had an idea based on a record 30 years ago that was called ‘Raw.’ And so there was an idea to sort of revisit our 30th year – it would have been 30 years since that record would have come out right now. I’ve done 30th-anniversary versions of all of our 80s albums and remade them as modern songs and see how they stack up etc. And the ‘Raw’ album was the one I never got to. I felt like 30 years ago; we missed a bit of an opportunity.

The ‘Raw’ album was the last album we made with the 80s line-up of the band. We had hit a time where our place in the world was affected. It was challenged by younger musicians like Nirvana and Pearl Jam coming through. We had put out our best stuff in 1990. And we thought we’re gonna have a big song with a cover of John Lennon’s ‘War is Over.’ We would have a male voice choir singing on it, and it was all sounding great. And then they wouldn’t play it because the Gulf War was coming. And it was like, well, how can we play a song called ‘War is Over’ when one’s just beginning. And I felt we’ve sort of lost control of who we were a bit as a band. We weren’t the first on the block and the new lads or the new sound anymore.

Our place in the world was being defined by outside influence. And so I thought with ‘Raw’, we had a chance to reclaim our identity, reclaim our place of worth. And I said to the band, we’d just met Neil Young not long before in December 1989, just before Neil Young released his ‘Freedom’ album. His manager Elliot Roberts came to one of our gigs. And he was representing The Alarm at the time. He said to us, “Look, Neil’s made this incredible album; it’s his best for a decade. He’s distanced himself from his audience, his critics. This ones gonna take him right back to the centre, and do you want to have a listen?” He gave us a cassette, and we played the album on the tour bus. ‘Rockin’ in the Free World’ was on it, and it was on it twice. By the time we played the album, I’d already written out all the lyrics, and we worked out all the chords, and we gave Elliot his cassette tape back. What a great album; Neil’s definitely going to smash it with this. Elliot stuck around for the gig. We walked for the encore, didn’t say anything and played ‘Rockin’ in the Free World’, and the place went crazy, you know, and nobody knew. They thought it was a brand new Alarm song. And Elliot came into the dressing room after the show and said, “Oh my god, Neil Young is gonna kill me when he finds out what you’ve just done.” But the opposite happened; Neil was really intrigued. And by the time we got to San Francisco, he came to the show; we went to his ranch the next day to sort of say hello and meet him. And we started talking about maybe Neil Young producing our next album, which would have been called ‘Raw’.

We were so inspired by hearing him play ‘Rockin in the Free World.’ By the time we got to the east coast, he actually was there again, and he jumped up on stage, and we played ‘Rockin in the Free World’ together. It was amazing. And that was our last act of the 80s, in a way. A few days later, it was 1990, and we started thinking about the future. And I think the conversation we started with Neil (to produce the album) never really went anywhere after that. I think to be fair to Neil; he could see that we were not quite so sure of ourselves where we were going. He was looking for some bands to do his thing with, and he went off with Pearl Jam and did ‘Mirrorball’, but in a parallel universe that could have quite easily been ‘The Alarm’ doing that (laughing).

So when we came to make ‘Raw’, I said to the band, let’s just make a record that re-establishes The Alarm. Let’s write ten ‘Rockin in the Free Worlds’ that talk about what’s happening and get back to the basics of what powered the band into the world in the first place and see what we’ve got. But by the time we got to the studio, that idea had dissipated into it well, you could only write three songs, and we think maybe Dave (Sharpe) should become much more of a lead singer than you now and give the band a different voice. I was like, okay, let’s give it a shot, but it didn’t really fire on the cylinders as it might have done. So I always felt that was a big missed opportunity, so when this situation arrived at post-COVID, post the Capitol Building occupation, and I thought, well, we’ve got a lot to write about. Let’s see if I can capture the Zeitgeist on a new record. I sort of already thought about making ‘War’ in the background, and I did have some songs floating around. But I dropped all those because they were in the past.

We had a song called ‘Moments in Time’, and I wrote another song called ‘Just Another Moment in Time’ to sort of answer it. And I thought that’s not what we want here. That’s just looking back. Let’s look forward. And so once I’d got the first song out of the way, ‘Protect & Survive’, I thought, okay, I’ve got about three days to come up with the next one before I need to have something. Then they just started flowing, and once I got in the groove, I sort of almost had everything within a week of writing, the whole thing really, apart from a couple of pieces.

The only real nod to the original ‘Raw’ album is the title backwards, and there was a cover on the record as I always wanted to have ‘Safe From Harm.’ I was playing all my vinyl in the lockdown. That song just leapt out the speakers. It’s that “serious, infectious and dangerous” lyric, and I thought that could have been written today – that that could have a place on the record. I did a flyer out to Benji Webb from Skindred, and he came back positive straight away. It was like, ‘wow, it never usually happens like that, but it did.

I was gonna ask actually – ‘Safe from Harm’, the Massive Attack cover – what prompted the choice to include that and why did you reach out to Benji in particular for that one?

Mike: Well, I am a big fan of the song, and when I started to think about doing it with The Alarm, in that idiom, I thought, the one thing that was special about the song was the duality of the voices, the male and the female, the opposites. I need to preserve that. It can’t be one voice going from the chorus into the spoken word section. It has to be two voices to really carry that song off with authority. I could change everything else and not use the bass part and all the iconic elements of the song, but that part, I need to make sure that is intact. I thought, who would be a good voice, and then Benji Webb just popped into my mind. I’d always been a bit of a fan, especially because I’d loved Dub War before that band broke up and then Skindred have a song called ‘Under Attack’, we’ve got an album called ‘Under Attack, and he’s from South Wales. I’m from north Wales. So, without meeting each other, our universes have collided because of song titles, because we’re from Wales, we’re on the opposite ends of the racial spectrum. And I just thought, well, this has just arrived in my mind. I’m gonna give this shot. If this came off, it would be perfect.

His manager had been in a band that had supported The Alarm in 1984. I just reached out to his manager, and he came back to me really positive. We went off on this story about having met in 1984. He was in a band called Geschlecht Akt who’d opened for us. He said I think Benji would be really up for this. He said, “I think he’d want to do more than just serious, infectious and dangerous.” I said, look, if he wants to sing the whole thing, I’m happy to let him be the vocalist, I’ll stand aside. And anyway, within hours, like me, he has his own set up in his home, and he was okay with doing the recording in isolation. He sent an amazing vocal back and, and he sang above me in places, and there were places where he could sing on his own. It was a beautiful little moment of synchronicity happening right in front of our eyes and ears.

Another song that stands out for me – ‘Crush.’ If you can give us some insight into that track Mike.

Mike: Yeah, to be honest, it sort of started quite innocently in a way. I was messing around with the guitar one morning. I come up with this guitar riff in the song, and I thought this could lead somewhere. When I was singing the song, I thought it’s quite a rock line, and I could maybe arrange it slightly like an AC/DC number or something. So I started singing the chorus to myself, and the words I had were, “bust your balls” (laughing). That’s what probably made me think of AC/DC. That just came out while I was working. ‘I’m going to bust your balls!!’ – oh, I can’t say that that’s not right for now. I went for a walk in the woods. I was playing the words over and over in my mind. What can replace ‘bust’, that can still have a really strong connection to the melody, still have that force, and that you can really throw it out vocally, that it carries the sort of feeling of the song and somewhere in the woods the word was playing over and over again. ‘Trust’ then ‘crush’, and I thought I could make that word work. Yeah, ‘crush.’

I could hear the whole rest of the song straight away, woosh, the door of perception had opened as they say, and I was there. “Crush your movement / crush our human spirit.” It just felt like we’d all been crushed, weighed down by the lockdown. So I thought we can push back against that and actually say we’re not going to lose our dignity. We’re not going to lose our humanity or tolerance. We’re not going to be crushed by the weight of the isolation we’ve all been placed in.

After The Alarm, reformed or rebooted in 2002, the output & volume of albums has been incredible. How have you maintained that pace of writing?

Mike: Well, I think if you look at it through the microscope, there’s probably 19 Alarm albums that have been made since The Alarm was born in ‘81. So, over 40 years, that’s an album every two years, pretty much really, which is probably par for the course. But what I think clouds the issue with The Alarm sometimes is we’ve got many side-project records or remakes of songs as live records. I’ve done records with Billy Duffy from The Cult, and I’ve done records that are soundtracks to plays or film soundtracks. I often say I don’t think there’s a record shop in the world that could cope with putting all of The Alarm records in one rack. We’d need a whole side of the shop, at least (laughing).

I just like making music, and I can’t stop making it. Ever since the internet came along, it gave me a voice to express the scale of a project. In the 80s, probably one of the things that broke The Alarm in ‘91 was our guitarist Dave Sharpe went off to make a solo record. He was busting to get out on tour with it when we were doing our last tour. It caused a lot of frustration for our band because we could have carried on touring a lot longer than we did. The record label had divided loyalties whether to back Dave’s solo record or The Alarm record. It caused a lot of tension. And of course, as soon as the press finds out that someone’s making a solo record in the ‘80s, it became the end. And there was no way back, especially when we were doing a ‘Best Of’ as well. It’s like, wow, they’re finished!

In relation to that, I wanted to check with you how true this story was in ‘91. When you were playing Brixton Academy, there are things that have been written to say that pretty much you announced on-stage to the fans and the rest of the band that this was going to be your last performance or that this is going to be the last tour. Is that really how it happened?

Mike: Yes, absolutely true. What actually happened on the day was that we would meet the next day to put the band to rest for a while. Dave Sharpe, our guitarist, his solo album was coming out in the next week. At the soundcheck, he announced that he couldn’t stay for the meeting tomorrow because he was on a 6 am flight to New York, and he was playing a show the next night in New York that had just come in – a big radio show for Earth Day and it was very important to him.

IRS records, our label were filming the show, which was all put together very last minute. It was at the end of a European tour, and there had been opportunities for us to maybe go on tour with Tom Petty in America and really carry the album forward in a proper way, but Dave didn’t want to do any more touring. And so, IRS organised a last-minute show at Brixton Academy. I think we only promoted it with two weeks’ notice, and then IRS wanted to film it, so they could have a video to keep promoting the album while there was no band to tour it. So that’s why the cameras were there. And so before we went on stage, I thought, okay, I’m going to tell it like it is with everybody here. It was mainly because I always thought we didn’t have a great relationship with the music press at the time. And at that time, in 1991, there was no internet, so your voice could only be heard through third parties. We’d had some run-ins with the NME, where they’d had two journalists come out to write about The Alarm, who wrote positively about the band, and then to find that their articles were getting canned because he didn’t meet the editorial policy of the NME. And so, there was a lot of mistrust in the whole situation, and Nigel, our drummer, had put Dave forward to be the lead singer on the last album. He’d sung three songs on the ‘Raw’ album, and then when we found out about his solo album, he’s got one of the songs on his solo album. So, is he using this record to promote his solo album?

Our agent had flown out to Germany to say Dave’s booking shows as the lead singer of The Alarm with another agent, and that’s why I can’t extend your touring, and he had every right to say he’s the lead singer of the band because he’d sung three songs on the last album. There was no truck there, but it was damaging to everything and everybody, probably even to himself in a way because he was raising too much expectation because for people who had turned up at the gigs thinking that it was maybe me they were gonna see, so it wasn’t helping anybody that situation.

What’s the relationship like with Dave nowadays?

Mike: Oh, really good. He comes on stage. He doesn’t want to be in The Alarm. He’s got that out of his system. He opens for us on pretty much every show we play, comes on for the encore. It’s great, you know. We’ve always had respect. Ironically, we never had a bust-up. In fact, when we were playing that very last show, I thought Dave was going to announce his departure from The Alarm. It’s not in the video film, because it wasn’t the whole concert, but if you listen to a tape of the whole concert that’s out there (on the bootlegs), just before Dave plays a song called ‘God Save Somebody’, which he sang on the last album. he messes up the intro. He got really nervous, and he introduced it as ‘One Step Closer to Home’, a big Alarm favourite. He wrote it. It’s my favourite Alarm song.

The crowd went mad, and Dave said, “no, no, no, it’s called ‘God Save Somebody”, and he went right into that song. And while I was on stage, in the back of my mind, I said to myself, “he bottled that there.” I really thought he was going to use the last Alarm gig to promote his solo album. I’m gone now. This is what I’m going to be doing. When it came to my turn, I just said that this is my last moment with The Alarm. I felt slightly unwanted by then. The band didn’t want me to write all the songs. The band didn’t want me to sing all the songs. So I thought, well, you carry on, and I’ll just declare myself unsafe, you know, smash it all down, and I’ll go and build something else where I can feel wanted. Well, I thought, was I courageous or foolish because I was walking away from a big livelihood that was a very safe situation. But I felt it had become too safe.

I don’t think internally in the band; we realised how much damage we were doing by changing things around without proper debate or proper creativity, genuine creativity driving the way we go forward rather than, okay, we’ll compromise. You can have that corner, and I’ll have this corner. That’s not the way to make great records or even decent records.

‘Eye of the Hurricane.’ It was the first Alarm album I ever bought as a fan.

Mike: You’re not the first person I’ve met who has said that. Many fans are fans of The Alarm to this very day that that’s the first record they bought. You know, the fans that bought ‘Declaration’ first. Sometimes, we lost a little bit of faith in those people in that early part of the 80s. That was our first real success, and many people bought ‘Declaration’ as their first Alarm album. They’d probably seen the band live before that record came out, and they felt it was a bit overproduced; it didn’t represent the raw edge of the band. Then next minute, they’re on Top of the Pops. Oh no, I can’t possibly follow them anymore. By then, people had accepted that The Alarm was a band that would go on Top of the Pops, and you didn’t have the politics associated with some of the elements that come when you’re a band coming out of the street, out of nowhere almost. People feel like they own the band, don’t they a little bit, which I totally understand.

I still listen to it. It’s a brilliant album. There’s a couple of songs I just wanted to touch on quickly. ‘Hallowed Ground’ – it’s one of my favourites from the album. It’s quite a magical, mystical Celtic piece. Where did that one come from?

Mike: Yeah, absolutely. Well, to be honest, the album before that – ‘Strength’, we toured extensively. I think we’ve been on the road pretty much from ‘84, ‘85, ‘86 without stopping because we’d started making the album in late ‘84. We didn’t get to produce the record in the way we would, even though we booked the tour to go with it. It was gonna be called “Absolute Reality”. And then the producer had to pull out, so we went on the tour, and we toured for almost 18 months between touring, straight into the studio, back out on the road, and had a lot of success. When we came home, we were returning home, the return for us was playing at Wembley with Queen, and we did two nights there. We played it for 25,000 people in LA. It was amazing, a dream come true. And I got home to Wales, and the last thing I wanted to do is pack another suitcase and go and stay in a hotel. And all through the tour, people have asked me what Wales is like? It’s, well, it’s a place I wanted to get away from, but now I’m answering the question, I think, wow – it’s a beautiful country. It has a great community spirit. I look out over the sea, and I look across the Irish Sea. It’s incredible. I started thinking.

Actually, it’s really good. I’ve got tired of being in London, trying to rehearse and write when you’ve got Motorhead on one side and Aswad on the other. You couldn’t think because of the bass rumbling through the walls. And so when I got home after all that, I was staying with my Mum and Dad, and it was right at the time when video cameras became accessible with microphones in them, and I’d always recorded my songs onto a Walkman before that. So I got home, and I decided to get a little car. I’m going to go on a journey of discovery. I’m going to visit Wales, where I come from, and I’m going north and south, east and west. And I took the car, and I took the video camera, and I used to drive around and find these amazing places, set up the camera and just start writing about what I could see. And at one point, I went to Mostyn docks on the north Wales coast, and I set my camera. I could see some abandoned shipping in the harbour and a few of the old cranes (that aren’t there now), but they were there, and I thought, what about what happened here..(singing) “Well, the docks lie crippled in the northern towns…” and it just came out, and I had it there and then. Later I went back and sort of transcribed it, and it became The Alarm song. But I suppose because it was all written in Wales. On all the songs on the album, you’ve got brackets, parentheses after the song, and that’s where the songs were written. I think ‘Hallowed Ground’ might say ‘Mostyn’ on the inner sleeve?

Vale of Clwyd.

Mike: Yeah, yeah. Well, that’s where I live, you see, and that’s above the Mostyn docks on The Vale of Clwyd on the coast. I went down there and wrote that song, and it was about coming home and seeing people that I’d grown up with were not in the town anymore – they’d gone. It had been the 80s, and it was the Norman Tebbit / Maggie Thatcher, ‘get on your bike’ era – if you can’t get a job in the crippled docklands, move away, get on your bike. Many people had left the community and were struggling in the cities trying to make a new life for themselves without the support and proper training, having to relearn new industries, all this sort of thing. And that’s really when the song was born, in those moments.

Love it. And then ‘Rain In The Summertime.’ Is it really about good old Welsh and British weather?

Mike: I don’t know, to be honest about that. Because when it was written, it wasn’t considered for the album at first. I thought we’d done all the demos. John Porter had been put forward to be the album producer. And there was some trouble in the band, make no bones about it in 1987. Dave and Nigel both stood up to Eddie and me, and when we came back to rehearsal, I had all these cassettes of new songs laid out on the ground. Dave and Nigel sat in the rehearsal room with us and said, “right, no more Mike Peter songs. We’re going to write the songs as a band, or not at all.” I said, okay then, well, where do we start? And they said, “what have you got?” I said, well, I’ve got all these songs, but you don’t want to use those. It became this stupid stalemate, if I can use that as a phrase these days. Dave Sharpe had a girlfriend, and a few days later, this big story erupted in The Daily Mirror that we had a bust-up, we were about to break up, and it was all contributed to Dave Sharpe’s girlfriend.

In those pre-internet days, we didn’t realise how much damage that did to the band. It went around all the radio stations; a big sort of shockwave in the rock news, you know, the latest news from Britain, The Alarm are breaking up! It made it very, very difficult for us. When we did come through all that eventually, we had to go and do another tour called ‘The Electric Folklore Tour’, and that was really to try and put the spirit back in the band.

The compromise and there were a lot of compromises in the early Alarm days. Our A&R man would choose the songs from our various demos. Nigel and Dave went off and did their demos. I did demos with Eddie MacDonald. We put them all into Steve Tanner, the A&R man who signed the band, who we all trusted, and said all of mine and Eddie’s songs to be on the album, apart from ‘One Step Closer To Home’ from Dave, which was leftover from the ‘Strength’ album. We hadn’t been able to record it properly from that album because of a certain Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin. That’s another story…IRS Records brought John Porter in. Because he’s done The Smiths and worked closely with Johnny Marr and gotten the best out of Johnny Marr, he became a producer to bring the best out of Dave Sharpe. That was the real reason. Count on Mike, count on everybody else, but we’ve got to build a bridge with Dave. Let’s bring in somebody who understands vintage guitars and really worked with him. He was a brilliant, brilliant producer. And right at the end of the sessions, when we’ve recorded all the demos and then pre-production, he said to me, “is there anything else you’ve got lurking around that you might have just thrown away in an afternoon and decided not to pursue?” So I’ve got this one cassette tape, and it’s got the words ‘Rain In The Summertime’ written on it. And I said it was just a bit of a throwaway jam while we were having a cup of tea, and Nigel had a drumbeat going on the drum machine that he had.

I love the drumming on that song.

Mike: Yes, it’s great, it’s brilliant, but it started with a drum machine beat. We’d met Jimmy Iovine, the producer. He didn’t produce the ‘Strength’ album; he almost did. He’s a big uber-producer now, but he said to me, “when you’re writing your songs, why don’t you get yourself one of these modern drum machines and write with that in the background. It might change the way you work.” Get on them, and off we go. Anyway, this bit of a tune with the words ‘rain in the summertime, and John Porter played it and it went on for about 20 minutes because I was singing the chords and the chorus, Dave was mucking about on the guitar and on the tape, you can hear Eddie go, “Dave, play that bit over and over again, a bit like Big Country”, he said. It was this mad, mad sort of tape. Anyway, John Porter said, “there’s something in this. Leave it with me,” and he had the cassette in his producer suite in the studio in Milton Keynes, where we’re doing the album. And he had an Atari in his room, the early computer and then one day in the sessions, he comes and says, “I’ve mapped out that tune you have all going on the cassette. So, here it is.”

And he played it back in the studio with a tune that he put behind it, and it was like, wow! This is gonna be amazing. It’s gonna be very different for The Alarm, but it’s gonna be special. So we got Dave to come in and play the guitar on it. Dave played one pass of the song, and John Porter said, “right, let’s go back to the beginning, and this is going to be amazing now.” We’ve got the riff now that we were thinking would be a bit Big Country. We’ve got it at the end of the song. So John said, “let’s do it at the beginning”, and Dave refused. He said, “No, what you’ve just heard, that’s genius, and I’m not going to change that.” And we’re like, “you made a mistake there.” And he wouldn’t change it. So, John Porter and I had to do a lot of the guitars, and John did an amazing job. Probably how he’d done ‘How Soon Is Now’ by the Smiths. He took samples of Dave’s part where he played it really well at the end of the song and dropped it in. It was proper rock and roll surgery.

Well, you wouldn’t know.

Mike: No, you wouldn’t know it’s incredible. In a way, Dave was right because there is part of it that is the moment of creation, that you can’t go back and do it again, but John Porter really just took the moment of magic and tidied it up and applied it. But then I had to go and sing it, didn’t I? I don’t like the words ‘rain in the summertime.’ That’s not The Alarm, you know, that’s not “Give Me Love, Give Me Hope.” It’s not “68 guns will never die”; it’s “rain in the summertime.” It’s a bit wistful for the band and me. I tried everything, and John Porter said, “no, Mike, it’s universal, it’s beautiful. What you’ve sung has come out of your subconscious. It’s fantastic!” In the end, I gave up and went, okay, I’ll sing it as “rain in the summertime.” I’m so glad I did.

I’m glad you did too.

Mike: It was obviously a subconscious thing from being in north Wales around that song. It’s not on the sort of video camera takes, but it was obviously the spirit of being in Wales writing in the summer. There’s a lot of rain, you get used to it being a Welshman, and that’s where it comes from.

You mentioned Big Country. Did you have a Big Country song that you loved to perform most?

Mike: Well, my favourite was always ‘In a Big Country’ or ‘Fields of Fire’, and then later I loved ‘Fragile Thing’ off the ‘Driving To Damascus’ album. I thought that was probably one of Stuart (Adamson’s) best songs with Bruce Watson – a beautiful song. There are so many great songs, which partly drew me to sing for Big Country. I’d known Stuart, and we played as The Alarm & Big Country in 1983. I briefly met him. I don’t know if he was still with The Skids, but he and his wife Sandra came to see The Alarm in 1982 in Edinburgh, at the nightclub above The Playhouse.

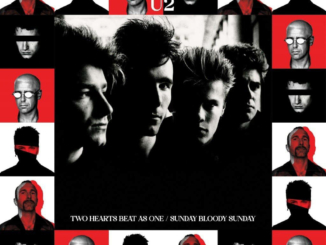

I’d seen him playing in The Skids, and I thought, what a talent. We properly met in ’83, and it was the last night of U2’s world tour, and we hadn’t played a gig together with Big Country at that point. That came a few months later. The night before, I’d gone to Brighton to meet U2 because we played some dates with them on tour, and I went to see them. Bono said, “do you want to come on stage and play a song?” I said, yeah, ok. What do you want to play? And he said, “we don’t know any covers.” I said, why don’t we play ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door?’, and I showed him how to do it. We went on and played it, and then Bono said, “that’s great, come tomorrow night. Let’s do it again tomorrow night!” We were actually the opening band playing with him at the Hammersmith Palais. So we did our set. And I was hanging around backstage waiting to go on for the encore, and Bono introduced me, and he said, “I’m gonna bring two guys on stage. They’re the new breed.” He introduced Mike Peters from The Alarm. I come up from the back of the stage onto the stage and Stuart Albertson from Big Country. Stuart was in the audience watching the gig, so the whole crowd lifted him and carried him over their arms, and I helped him up onto the stage, and that was how I first met him, and I shook hands with him. He got a guitar we played, and then at the end of the show we were signing autographs at the side of the stage, and we got on fantastically well, so we played some gigs together.

And then when I was bringing The Alarm back into being in 2000, it was originally going to be starting the whole band again, to be honest. Eddie and I wanted to reboot The Alarm, and Nigel and Dave permitted us to go ahead. We did our first gigs with Big Country with Eddie and me because no one would give us a chance as it wasn’t the original line-up again. It was Mike and Eddie; it’s been 10 years, so no one gave us a chance. But Stuart Anderson said, “look, they were good to me. I want to have them on tour, so let’s take them on the Big Country tour.” And then Eddie made it through about eight shows and realised he’s ten years out of rock and roll. He preferred being off the road rather than on it. So he bailed really and left it to me. And that’s how I’m the last one standing in The Alarm. Stuart was great to have given me that opportunity when not many people would, and even on the last few dates that I was playing with Big Country with The Alarm, the new Alarm, they said, why don’t you come on a European tour. I know you probably can’t bring the band, but you can come on your own with a guitar and travel on the tour bus and open the shows, so I did. I get on stage with them every night we play “Rockin’ in the Free World’ or something else, and I could see Stuart was struggling with it. It was the Final Fling. He had announced his departure. And he kept saying to me, “Look, Mike, you should carry on with the Big Country. They need a singer. It’s just me leaving. I don’t want to break up the band. I think it’d be great for them to carry on with you.” I was like, you don’t mean that, Stuart, you know. And anyway, we were having some conversations about working on another kind of project and then he took his life. Sadly, we never got to conclude our friendship and take it to the place we thought it might go.

In 2010, I was climbing Snowdon with our charity, and Bruce Watson phoned me up and asked me if I’d sing on a couple of songs with Big Country at a tribute concert – something to do with Steve Lillywhite. Yes, of course. I would be honoured to be a guest. I didn’t hear anything for about three weeks, and then he called me back, and I said, oh, what’s happened about that gig? He said, “it’s not happening now, but you were so enthusiastic about it that we booked the whole tour for 2011, and it’s going to start on New Year’s Eve in Glasgow.” I thought, what a baptism of fire, singing for one of Scotland’s most iconic bands in Glasgow on Hogmanay.

No pressure.

Mike: No pressure! And so at that point, I went back and looked over my history with Big Country, and I watched the Final Fling show that had been recorded in The Barrowlands. That was Stuart’s last proper gig with Big Country. I was watching it, and something was niggling at me, and I thought, what am I missing here, and there was a close-up, and I realised that on his last ever gig, Stuart was actually wearing a Mike Peters t-shirt that he got from my merch booth. So I thought, oh, that’s kind of meant to be, really. All the signs were there. So when I was singing ‘In a Big Country’, because of my cancer diagnosis in 2005, that was a song that came to me when I had an incident in my first moments of treatment. It was quite heavy, and I was sort of passing out because of shock. Jules put my headphones on to try and give me something to hang onto, and ‘In a Big Country’ came on randomly, and when it said “Stay Alive”, I thought, that’s what I’m gonna do, I’m going to stay alive. So I’ve always loved that song, and I did a documentary for American TV called ‘The Song That Changed My Life’ and I chose ‘In a Big Country.’ Good documentary. Quite a little story behind it.

Your charity, Love Hope Strength, sounds like a fantastic organisation you put together there. Can you tell us a little bit about it and the Everest base camp trip with some other musicians?

Mike: Yeah, absolutely. When the charity started, it was really between myself and my wife Jules and a friend of mine who helped me out when I didn’t really know what a bone marrow transplant was, and I was looking at that, contemplating that as a route back to health. He was from America and really helped me in a great way. Together we started talking about a charity and what kind of charity to do. Because we both came through and arrived at health through different healthcare systems like the NHS in the UK and the private health care insurance in America, we realised that there was a lot of people who didn’t have access to the kind of treatment that we’d arrived at through our various protocols that existed in the countries that we live in. So let’s do a charity to give back.

I always wanted to pay back the nursing team who saved my life. There was a friend I knew from a long time ago. He had the first bone marrow transplant in north Wales. His name is Peter Large. On the day I was having treatment, it’s very near Christmas, just a day before Christmas Eve. And he came to the hospital with funds that he raised through his estate agent, things for the staff, things for the patients, frontline help, simple things, even some books and some information, some money to buy things to ease the passage through the chemotherapies the patients go through on the front line. And they said Mike’s having treatment today. It’s his first day, and Peter sat down with me for a minute. He said, “look, Mike, when you come through this, you’re gonna want to give back like me. Don’t give it to the big charities where it ends up in a black hole of admin. Bring it to the front line right here.” That stayed with me, and when I did start our charity (Love Strength Hope), I wanted any fundraising to benefit the front line, so I thought I’m gonna climb Mount Snowdon in Wales, and with the money we raised, we’re going to give it to the nurses right there and then. We’ll have a say in how it’s spent that way, which was great.

Then, with my friend (James) from America who’d come from Texas, he loved the idea and said, but we’ve got to go to Everest. After all, they need it more than our communities possibly, because they don’t have anything. And so we went to Everest. It was on a wing and a prayer, to be quite honest. It was James, Jules and I making phone calls to the trekking companies. We want to bring some musicians, where’s a good hotel? Have you got any guides? It was absolutely crazy, and by the next minute, we had VH1 come on board to give us some money to film it all because it sounds like you probably lose your life.

I think they felt the jeopardy would be great (laughing). We managed to pull it all together. We got Glenn Tilbrook from Squeeze to come, Nick Harper and The Fix (British band that had done well in America), and Slim Jim Phantom from The Stray Cats – an old school friend of mine, and that’s how we rolled. We nearly had Jimmy Barnes from Australia, but he had to pull out to have heart surgery. It really was a shaky expedition, but, ah, it was absolutely life-changing when we got there. We walked through the Khumbu Valley and saw these kids with nothing, but they were so happy. They had everything because they have nothing. When the word got out about these mad guys, we had Sherpas helping us carry our guitars and all this kind of stuff. We got to the Sherpa capital in the Khumbu Valley. Suddenly, Nepal’s people were realising that we were actually raising funds to help build onto an existing cancer centre in Kathmandu, called the Bhaktapur Cancer Centre. They couldn’t carry our equipment far enough.

Then we did a gig in a bar in this place, and all these villagers were coming over the mountain to see these mad Westerners with guitars, and we had people climbing under the roof. Glenn (Tilbrook) took us on a walkabout to sing to everybody in the room, and we had to climb over billiard tables with the guitars, and it was amazing. At the time, we actually played the highest gig globally, above base camp at a place called Kala Patthar. We actually broke a lot of ground. We took a friend of ours and did a lot of work on our website, and we pioneered making DVDs. So we actually went and did live podcasts from Everest no-one had ever done before. And Tom, our friend, ended up being hired by the biggest climbers in the world after that. He hated it. It was that altitude, the sickness he couldn’t stand it. But the following year, he was there working for (mountaineer) Ed Braeshears. Tom lived at base camp for three months! So we brought a bit of rock and roll to Everest in our own way. The King of Nepal threw a concert for us in Bhaktapur in Durbar Square in Kathmandu. We had about 30,000 people show up. Now that was an absolutely incredible show, incredible! Glenn Tilbrook was playing bass, rocking out, and he had lost so much weight on the mountain that his trousers fell down (laughing). We ended up buying the first mammogram machine to check out for breast cancer in Nepal without flying to India to get into that they could be near their family and their support network.

We keep supporting them to this very day, especially after the earthquake hit. James Chippendale set the charity up with me. He was very good friends with Chester (Bennington) from Linkin Park, who also took his own life. We’ve been doing ‘bone marrow drives at Linkin Park shows. We saved about 47 lives and found matches for people through their fans register on their gigs. “Music Relief Charity” is Linkin Park’s charity. Between ourselves and them, we did a non-cancer fundraising project together that raised a quarter of a million to go down to help Nepal after the earthquake because it’s got a big place in our hearts.

Thanks a lot, Mike; it’s been a lovely chat; I really enjoyed it. Good luck with the album.

Mike: It’s great; it’s rocking out there. It’s been a great response. I found out that there’s a chart out there for all the bands over five years old who get classed as ‘retro’ bands. ‘War’ is in the Top Five albums by a band that’s over five years old in the world at the moment. All the digital stuff that is going on, it’s great because we never put a record out digitally first. We generally support our physical buyers and then put it out a few months later on. But this one just came out straight away, so it’s been great.

Be the first to comment